Want a two-month summer job that’s ten hours a day, seven days a week, perched atop sheer cliffs in freezing rain snaring seabirds off narrow ledges? Then this job’s for you: field assistant for the Norwegian Polar Institute in Ny-Ålesund, Spitsbergen Island. Icelander Saga Svavarsdóttir and Frenchman Delphin Ruché wouldn’t have it any other way. “We are lucky to have this job,” says Svavarsdóttir. “We work more hours than we have to and stay out in the field as much as we can.”

On a typical day, they cut across stormy seas to Ossian Sars, once connected to land by glaciers until ice began rapidly disappearing in the late 1990s. As we hike up the back side of mountain cliffs, the terrain becomes grassy and green, fertilized by guano. This is paradise for foxes, skilled climbers who prey upon kittiwake chicks, often pushed from ledge nests by larger siblings. Days earlier I watched a hungry fox with pups chewing on a kittiwake wing near this same site.

Topping a blustery ridge, we scuttle down slippery, grass-covered hummocks and boulders to the edge of precipitous cliffs overlooking a foggy fjord clogged with ice from calving glaciers. Kittiwakes and Brünnich’s guillemots, or thick-billed murres, crowd sheer ledges and fill the frigid air with shrill complaints and deep groans that sound like a mix of wild children screaming and demonic clowns laughing.

Sliding over a cliff on a rope tied around a boulder, Ruché lowers a pole with a snare on the end and expertly snags a guillemot by its neck. He whips the pole skyward to Svavarsdóttir who grabs the noose and deftly loosens it while cradling the bird in her lap, stoically ignoring a nasty cut on her hand delivered by the guillemot’s sharp beak. Ruché joins her topside and the pair weigh, measure, band and blood-sample the bird before lofting it back to its comrades below.

By day’s end they sample four birds and log hours of notes on individual nests, eggs and chick survival. Their efforts help scientists monitor the health of seabird colonies by measuring breeding success, blood toxins and hormonal balance. As climate change brings warmer waters and consequent shifts in zooplankton and fish populations, several cliff-nesting seabird species have suffered, placing them on the brink in more ways than one. (To view a video of their work, see VIDEO REPRISE: On the brink.)

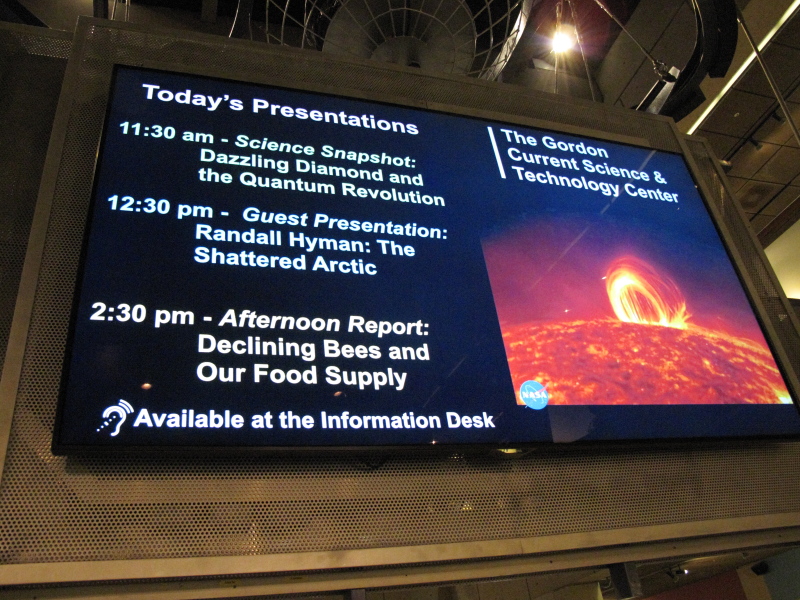

CLICK PHOTO AND GO TO THE BRINK:

Field tech releases guillemot after weighing and sampling blood and feathers atop cliffs of breeding colony. © Randall Hyman