Aside from coal and the University Centre, which specializes in Arctic studies, tourism is a major revenue earner in Longyearbyen. From snowmobiling to dog sledding to ice caving, Spitsbergen Travel (www.spitsbergentravel.com) is an easy one-stop-shop for accessing and arranging tours with the various companies specialized in each activity. Guests are given the opportunity to take on as much of a challenge as they like, and excursions can be four hours or four days.

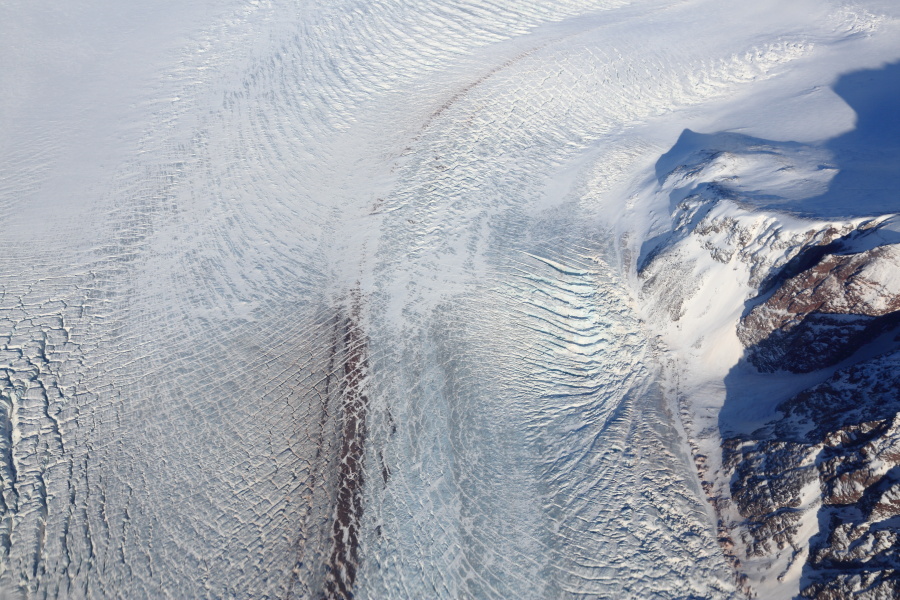

Dog sledding includes learning how to fetch your own team and harness it before hitting the wide open spaces. Ice caving requires suiting up with crampons and spelunking helmet before squeezing down ladders into an underground glacial river channel. Snowmobile tours travel to distant fjords and wilderness.

It seems all fun and games, but talk with a guide long enough and you’ll often hear uneasy references to changing weather patterns and how it may affect the tourist season. Early ice melt floods glacial caves, slushy snow and early break up of fjord ice cuts into snowmobile travel, and less snow overall makes dog sledding a challenge. It’s all happened occasionally over the past decade, but seasonal cold has returned each time to save the season. Nonetheless, locals have begun wondering what the future holds in store.

CLICK ON PHOTO BELOW TO HIT THE TRAIL: